#03 TRADITIONAL JAPANESE ENTERTAINMENT

Each edition of EJP Newsletter will include a special column in which the motifs depicted by PICTOGRAMS are explored in a little more depth to give you further insight into the multifaceted charms of Japan. The third edition features engei, a traditional form of Japanese entertainment.(Photos are posted with permission from Shinjuku Suehirotei)

Origin of comedy in Japan

Japanese TV stations and Internet video services broadcast a wide spectrum of comedy shows and dramas catered to people of all ages from manzai and comedy skits to impersonations to rakugo and ogiri(where professional rakugo storytellers use word play to comedic effect). These have been indispensable forms of entertainment for Japanese households for many years. Art forms like these performed in front of a crowd are called engei in Japan, which in its broad sense includes theatrical, dancing, and singing performances, but in its narrow sense refers to traditional vaudeville shows, such as rakugo and manzai, performed in engei halls(or yose)for the common people.

What kinds of entertainment did people enjoy in ancient times? Japanese love of comedy is said to date back as far as 1,400 years ago when a variety of performance arts, such as juggling, acrobatics, and buffoonery, called sangaku were introduced from China. Sangaku in those days was similar to our modern-day circus. It entertained people with fire breathing, sword swallowing, mimicking of fish in water, and so on. and thus was also called hyaku-gi (百戯, one hundred entertainments) or zatsu-gi (雑技, variety arts).

From Sangaku to Kyogen—the oldest comedy in Japan

Sangaku from China became popular particularly among aristocrats in the Nara period (CE 710 to 794) due partially to its novelty. According to historical records, sangaku enjoyed protection by the imperial court along with gagaku (Japanese imperial court dance and music) and was performed at the eye-opening ceremony of the Great Buddha of Nara in 752.

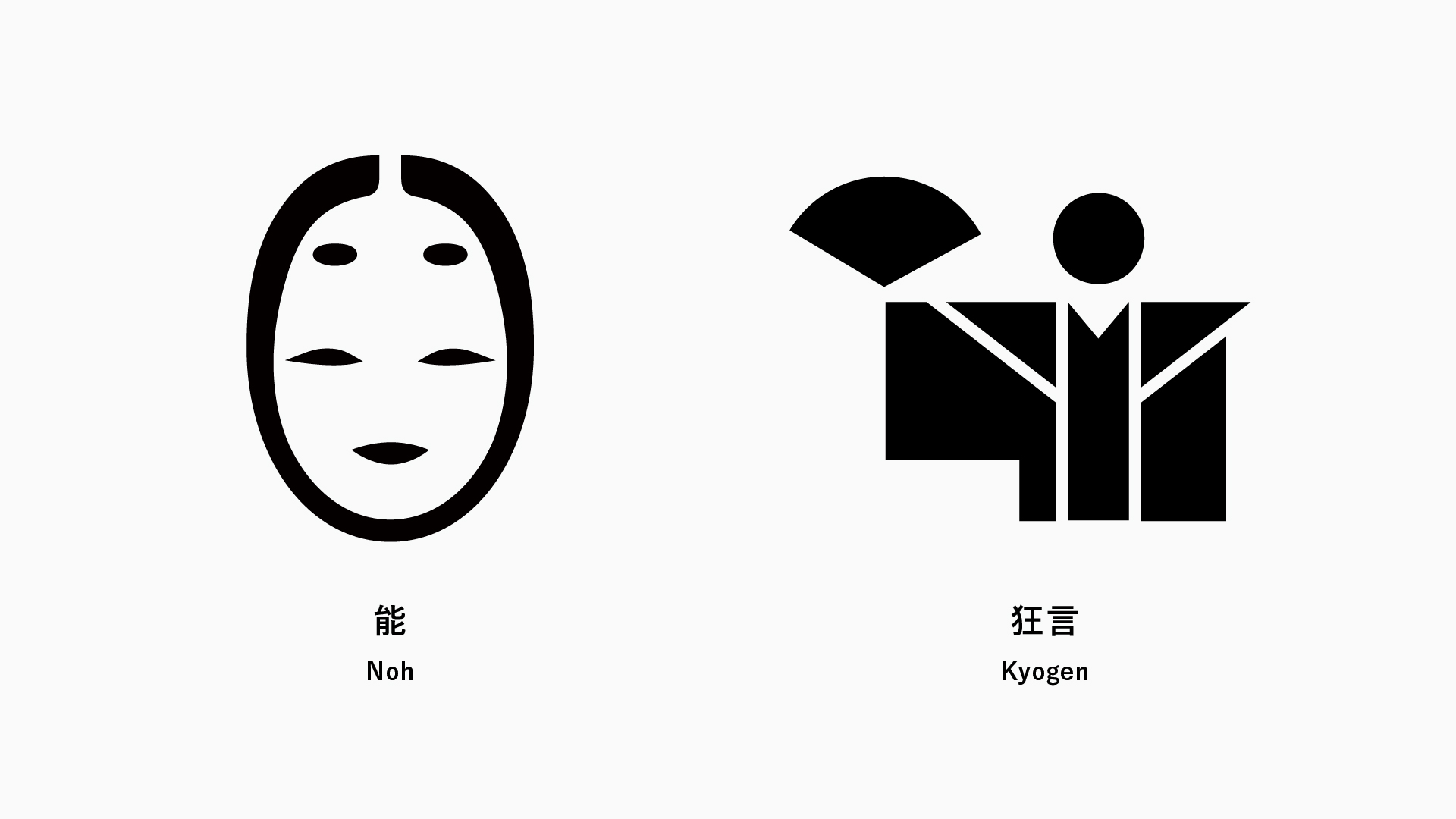

However, after being released from imperial protection, sangaku chose the path of popularity by performing freely on the street for the commoners. It gradually mingled with indigenous traditions and developed into an art form called sarugaku (猿楽, literally monkey music), which further evolved into Noh (a theatrical art form of sophisticated dance and song) and kyogen (a spoken theater that inherited comical elements from sarugaku). Kyogen that comically depicted the everyday lives of ordinary people is said to be the first art of laughter established in Japan. This influenced kabuki and other subsequent forms of entertainment.

Dawn of storytelling art—the emergence of otogishu

During the Edo period, kyogen became a refined art of laughter for the upper class after being officially designated as shikigaku (ceremonial dance and music) and bestowed the patronage of the Tokugawa shogunate. Meanwhile, separate branches of entertainment for commoners began to emerge—namely, rakugo and kodan storytelling.

The roots of these storytelling arts can be found in the profession known as otogishu that played an active role during the Sengoku period (Warring States period). Otogishu were scholars, tea ceremony masters, and other persons of wisdom hired by daimyo (territorial lords), such as Takeda Shingen and Oda Nobunaga, as conversation partners to broaden their knowledge and perspectives and relieve the stress of prolonged wars. In an effort not to bore the daimyo, otogishu told stories full of wit and humor (known as kokkei banashi).

Two of the most renowned otogishu were Anrakuan Sakuden, a Buddhist priest and an advisor to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Akamatsu Hoin, who served Tokugawa Ieyasu. Sakuden was the author of Seisuisho (醒睡笑, Laughs to Wake You Up), a collection of humorous anecdotes considered to be the origins of many rakugo stories that are still performed today. Hence, he is known as the founder of rakugo. In contrast, Hoin told epic military tales (gunki) like Taihei Ki(The Record of Great Peace) and Genpei Seisui Ki (The Rise and Fall of the Minamoto and the Heike) and is revered as the father of kodan.

Rakugo sprouted simultaneously in three cities

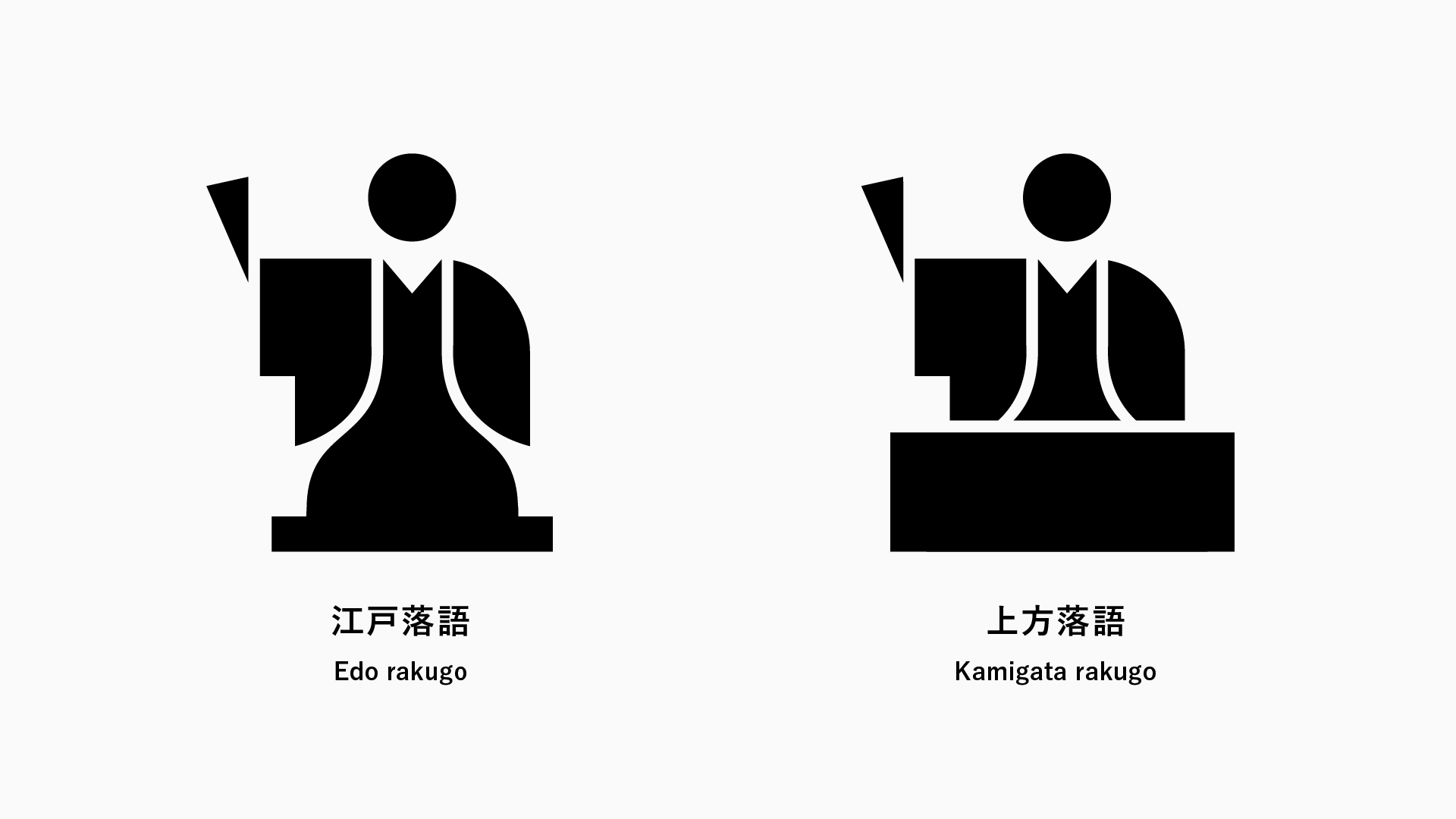

In the subsequent and peaceful Edo period, otogishu lost their role as advisors to war lords. Some therefore began entertaining people on the street with kokkei banashi and gunki tales in exchange for compensation. Stories thus told on the street became known as tsujibanashi. Tsuyuno Gorobe in Kyoto and Yonezawa Hikohachi in Osaka, the two most famous tsujibanashi storytellers, emerged at almost the same time and gained popularity, leading them to be called the founders of Kamigata rakugo (Kamigata being the area encompassing Kyoto and Osaka). Meanwhile in Edo (old Tokyo), Shikano Buzaemon, the founder of Edo raguko, began indoor storytelling (zashiki-banashi) at the invitation of various families and built a simple hut to tell funny stories to the general public for a price.

While Kamigata rakugo originates in street performance, Edo rakugo evolved from indoor storytelling in tatami-mat parlors called zashiki. The difference in origin between the two can be seen in the use of kendai (a small table set) and hyoshigi (wooden clappers) in Kamigata rakugo. Since early-day Kamigata rakugo performers told stories mostly on the street, they had to make loud sounds and use exaggerated gestures to draw the attention of passersby. Edo rakugo performers, on the other hand, performed their pieces in zashiki, which enabled them to concentrate on telling stories with details and subtleties to an attentive audience.

Birth of yose

Rakugo performances, which were given outdoors or in private homes in the early days, began being offered to the general public for a fee inside dedicated structures called yose in the late 18th century. The term is derived from the verb yoseru (to attract lots of people). The simple huts where engei was performed were initially called yose-ba (place) or yose-seki (seats), which were gradually and eventually shortened to the term yose.

While kabuki was also a popular entertainment around that time, it was a bit too luxurious for most commoners. Rakugo yose, on the other hand, was available for the price of a bowl of soba noodles sold by street vendors and thus gained great popularity mainly in Edo and Osaka. By the late Edo period, there were said to be a few hundred yose theatres in Edo alone.

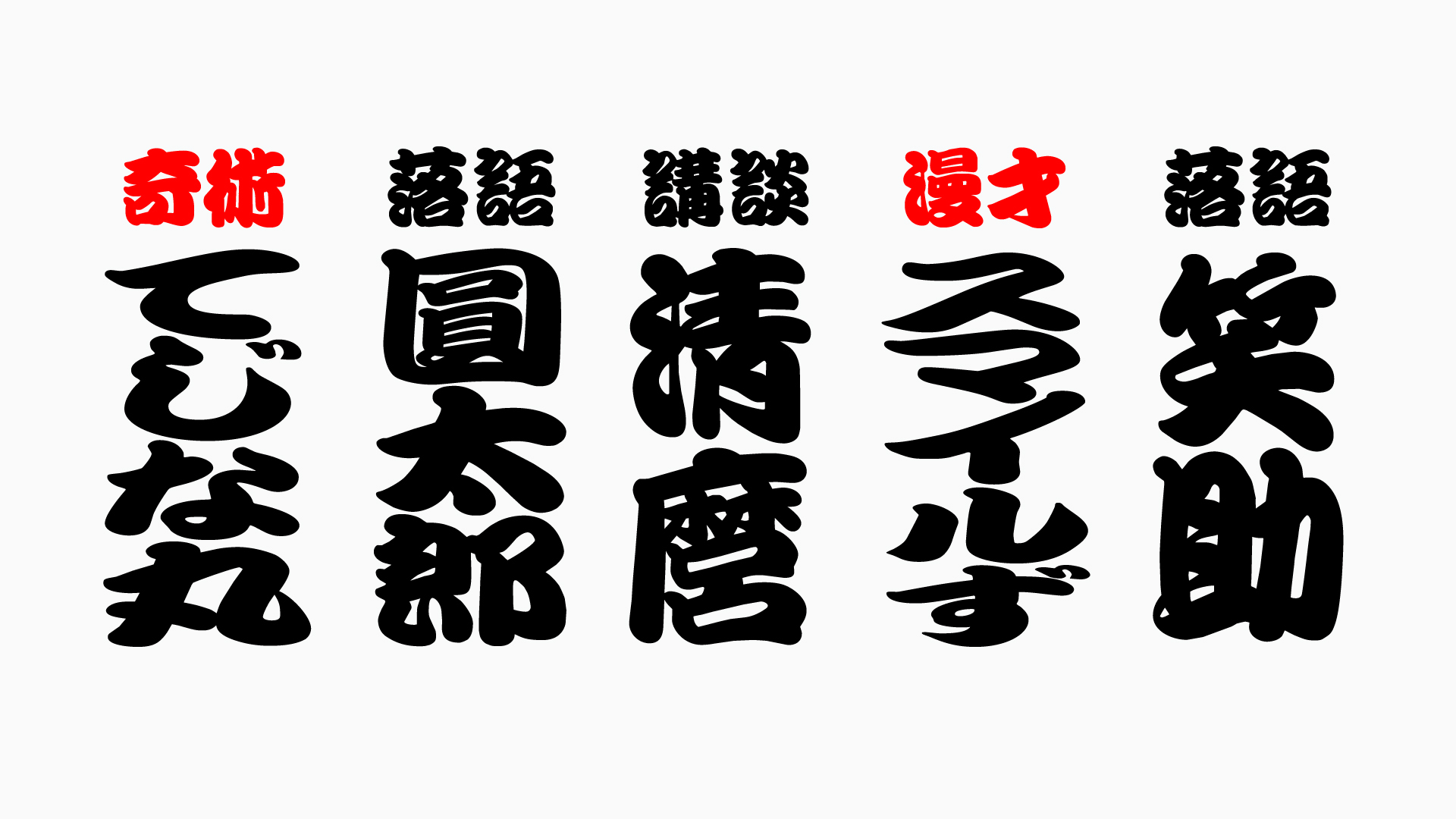

Yose made more colorful by iromono

Rakugo and kodan were the main acts performed at most yose, where music, acrobatics, magic tricks, and various other forms of entertainment were also exhibited as a change of mood during the intermission. They were called iromono (iro meaning color), as they added color to the program lineup. If you look at a program list posted at a modern yose, you will notice that rakugo and kodan are written in black while iromono are marked in red. The difference in color is rooted in this history. The now very popular manzai (comic dialogue) was also one example of iromono.

The unbeknownst roots of manzai

Manzai (漫才), which began as an example of iromono, did not initially use the style we know today. It is said to originate in manzai (written in different kanji, 萬歳), a traditional art of speech and song/dance for the New Year celebration performed to wish for prosperity and longevity from the Heian period about 1,000 years ago. Ancient manzai was generally composed of a pair of performers called Tayu and Saizo, who went from door to door. Tayu would sing festive songs while dancing with a fan, and Saizo would chiming in with silly remarks using a small hand drum. These remarks were then corrected by Tayu, very much like the exchanges between tsukkomi(straight man) and boké (funny man) of modern-day manzai.

From manzai (萬歳) to manzai (万才) to manzai (漫才)

It was after the beginning of the Meiji era when the ancient form of manzai for New Year’s celebration took the turn toward entertaining the populous. Some of the early manzai entertainers included Tamagoya Entatsu, a chorus leader of goshu ondo (a traditional Japanese dance song) who gained much popularity by performing goshu ondo on stage that integrated the exchange between Tayu and Saizo. Such dance/song performances mixed with the comical elements of manzai (萬歳) were called manzai (万才) until a revolutionary duo, Yokoyama Entatsu & Achako, burst onto the scene in the early Showa era. They made people laugh just by talking without singing or dancing and established a talk-show-style manzai(shabekuri manzai) that became mainstream among the succeeding generations of manzai entertainers. Various kanji characters used for manzai were unified into 漫才 around this time. Manzai has become the main acts of yose, especially in Osaka following the establishment of Yoshimoto Kogyo (a major agency for comedians).

How to enjoy engei today

Before WWII, there were over 100 yose theatres in Tokyo alone, most of which disappeared one by one with the diversification of entertainment and the diffusion of movies and TV programs. Nevertheless, a few dozen engei halls survived the change of times in different parts of Japan, including Suzumoto Engei Hall in Ueno, Suehirotei in Shinshuku, and Namba Grand Kagetsu (NGK), or the Palace of Laughter, in Osaka, where you can enjoy a variety of traditional and contemporary engei. On your next holiday, try visiting one of these venues and see the performers of various colors live on stage and experience the essence of Japanese culture for yourself.

Different Types of Shinkansen Trains in Japan

RAKUGO

Rakugo, one of Japan’s traditional storytelling arts, dates back to the Edo period and remains popular today. The performer sits on stage and tells comical stories that end with a narrative stunt (punch line) known as ochi or sage. A single storyteller portrays many different characters by using different voices and gestures. Broadly speaking, there are two major places of origin for rakugo, one being Edo (present-day Tokyo) where stories were told indoors (in tatami-mat parlors called zashiki) and the other Kamigata (the present-day Osaka/Kyoto area) where performances took place initially outdoors. Today, rakugo continues to attract new fans by offering new styles of rakugo performances in mini-theatres, etc. Ritsu, an avid visitor to rakugo shows, is never bored even though he knows exactly how the stories unfold and end because they are told differently each time by different performers—very much like classical songs that are still appreciated today.

KODAN

Kodan is another form of traditional storytelling with a history of over 500 years. Unlike rakugo, whose stories consist mainly of conversations between characters, most kodan stories depict warlords or other well-known historical figures. A kodan performer sits in front of a pedestal called a shakudai and reads out stories while tapping the shakudai with a paper fan (hariogi) to keep performer’s rhythm going. Kodanbon (books containing kodan stories) became very popular during the Meiji era. Among the publishers of kodanbon was Kodansha Ltd., a major publishing company today that earned its present position with the success of kodanbon.

ROKYOKU

Rokyoku is a genre of narrative singing accompanied by the shamisen(three-stringed lute) also known as naniwa-bushi. A rokyoku artist tells a variety of stories filled with drama and emotions in distinctive fushi (verses) and tanka (story lines) in perfect sync with ever-changing shamisen melodies. Rokyoku began originally as a street performance but later developed into yose-gei (vaudeville art) and became one of the three major traditional storytelling arts of Japan along with rakugo and kodan. Have you ever heard of a contemporary rokyoku singer named Takeharu Kunimoto? He sang rock and ballad songs with the shamisen. His early death was a huge loss to his fans and the music world.

MANZAI

Manzai is a traditional style of comedy usually involving two performers—a straight man (tsukkomi) and a funny man (boké) exchanging jokes in a variety of tempos with unique words and gestures. The M-1 Grand Prix, the most prominent manzai competition in Japan, is held annually around New Year’s Eve. Which duo will win the Grand Prix and grab a chance at stardom this year? Thousands of aspiring manzai performers are honing their skills as we speak to make more people laugh than their competitors.

DAIKAGURA

Daikagura is a lineup of dance and other eye-catching numbers, such as shishimai lion dances, shinadama*1,kyokumari*2,and plate spinning. Originally, daikagura was performed by the Shinto priests of Ise Jingu and Atsuta Jingu shrines who traveled around to offer sacred lion dances to ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune. Gradually, entertaining elements came to the fore and gained popularity as yose-gei (vaudeville shows) by the end of the Edo period. Until recently, on New Year’s day, typical Japanese households used to watch on TV the famous brother duo Somenosuke and Sometaro Ebiichi spinning a ball and other colorful objects on a traditional Japanese umbrella while calling out festively “Omedeto Gozaimasu! (Happy New Year!)” Sadly, both masters are now gone. Japanese New Year has not been the same without them.

*1 Shinadama: juggling of balls, knives, etc.

*2 Kyokumari: ball acrobatics

KIJUTSU

Kijutsu is a traditional Japanese magic performance that entertains audience with tricks, effects, and illusions. Its origin can be traced to sangaku (various entertainments) from the Nara period. Kijutsu uses a variety of tools from large-scale stage sets to small gadgets for sleight-of-hand manipulations. Kijutsu performers (kijutsu-shi) are eager to entertain not only by showing tricks but also with stylized movements not seen in Western magic and by engaging the audience in enlivening conversations. In an attempt to see through the tricks, Ritsu has been staring at the kijutsu-shi’s hands as hard as he could but to no avail. His moves are as fast as lightning—no wonder kijutsu was also called tezuma (hand lightning) in the old days.

KAMIKIRI

Kamikiri is the traditional improvisational art of papercutting. The performer solicits suggestions from the audience and quickly cuts a blank sheet of paper with scissors to create the suggested image or figure. Kamikiri is said to have started as a party stunt during the Edo period. Kamikiri artists possess great verbal skills because they keep talking to themselves or with the audience while cutting the paper. The finished work is usually offered as a gift to the person in the audience who gave the suggestion. Because of this rare exchange, kamikiri can engage an audience beyond words and is highly recognized and appreciated in different parts of the world, although it is not nearly as widely known as anime or manga.

MONOMANE

Monomane is the art of mimicry. Monomane artists mimic the voices and gestures of different animals, renowned personalities, etc. It is said to originate in kowairo-zukai(performers who impersonated the voices of Kabuki stars) and established itself as an art form in the late Edo period. Nakimane, a genre of monomane that mimics animal sounds, was also popular during the Edo period. Today, Edoya Nekohachi, a fifth generation animal mimicry artist, keeps this unique and refined art form alive. Ritsu was able to overturn his reputation as a crybaby by impersonating his classroom teacher perfectly. He is now regarded a hero.

KONTO

Konto refers to a short comedy sketch in Japan. The word is derived from the French word conte meaning a tale or fable. Unlike manzai, which mostly consists of dialogues between two performers, konto is a drama that takes place based around a certain situation, where characters in costume and makeup play their respective roles. Konto often uses stage sets, props, background music, sound effects, and just about anything else to entertain audiences. TV konto series, such as the legendary Hachi-ji dayo! Zen’in shugo(It’s 8 o’clock! Everyone come together) and Ore-tachi hyokin-zoku(We are the silly ones), were at their prime during the 1970s and early 1980s. Aiko’s father, an avid lover of comedy, takes pride in the fact that he grew up watching these programs in real time.

References (in Japanese)

・Kotobank

・Yamamoto, Susumu. Rakugo Handbook, 3rd edition. Sanseido.

・Otomo, Hiroshi. Enjoying Japanese Traditional Entertainment, Raguko and Yose-gei. Kaisei-sha